Why study algos

Preface

This post is really meant as a very soft introduction to what algorithms are. There’s hardly any technical content and it’s really just a frontmatter to keep my content self-contained. Also, some very basic background in Python is required but really you can get the hang of it just a few posts in, I’m sure.

Do I need a math/programming background?

It would help! But I’ll also do my best to keep it as self contained as possible. Feel free to skip parts that are already too easy, but definitely make sure you at least understand it before moving on. In the next post I will be talking about what exactly I’m using Python for (and more importantly, what I’m not using it for).

At the minimum, you should know about the following in Python:

- basic arithmetic operations

- if/else statements

- functions

- classes

- while/for loops

As for math, about high school math should be enough. You’ll need a little amount of calculus eventually but for the initial parts we’ll keep things informal.

Is this first post really necessary?

Depends on what you want to get out of it. I think most people might benefit from learning some algorithms first before coming back to this post to reflect on what I’ve said here. At the same time, I think this post is actually the most important for people who wish to see algorithms in a deeper sense. So my suggestion is for you to read this page to just familiarise yourself with what’s been said here, before circling back after having read much more of the content that I’m putting out before thinking back on what’s been said here.

Design Philosophy of this Series

I have a few lofty goals, and I’m going to try to accomplish all of them. That’s probably not the best idea, but here goes:

- I’ve spent a lot of time studying algorithms, and I feel like it’s a shame that a lot of algorithmic ideas aren’t made accessible to the general public. So I want to post about all that I’ve learned, and hopefully there’s something for people of all backgrounds.

- I want to make learning algorithms really fun. I can’t always do that when I need to cover the technical stuff (which I also want to do), but at least the basic ideas themselves should be easily explainable.

- I want to make a course (of sorts) on algorithms, but at the same time have it really informal, and very open ended.

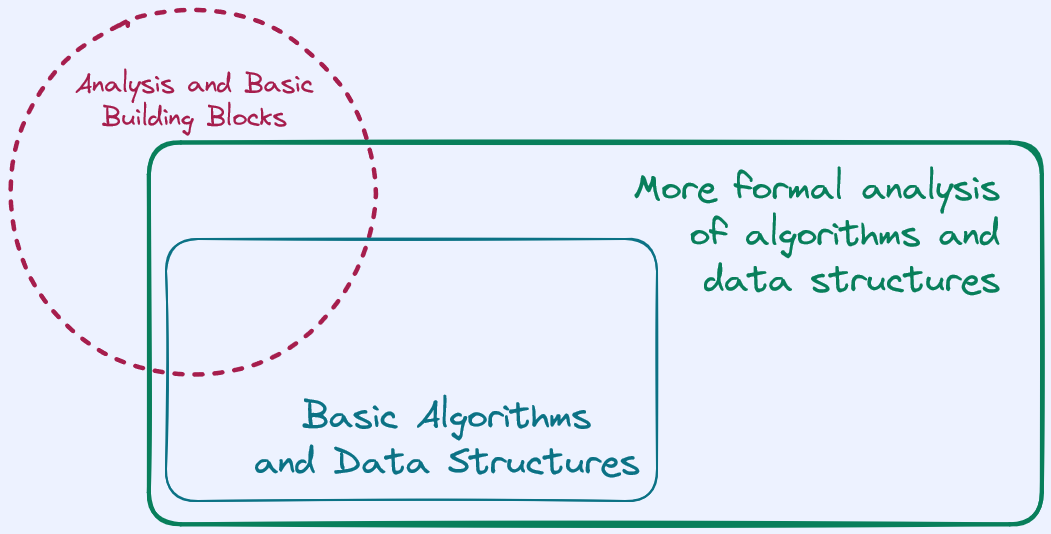

So the way I’ve decided to go about covering algorithms is roughly in 4 sections:

-

There will be an initial section that preps you on 90% of the background you’re going to need so that we’re all on the same page when we start talking about algorithms. This will be packed into a single post so that it’s easier for future reference. This section will not really talk much about algorithms, but all the stuff around it.

-

We’ll go through some basic algorithms and data structures to build up a toolbox. In this stage, we’ll take a less than formal approach. The idea is to build up some familiarity with the ideas and intuition.

-

We’ll revisit some of these ideas, but with a much more formal approach, so that we can see old ideas in a new light.

-

We’ll start talking about a much wider class of algorithms. Algorithms in the wild, algorithms for different settings. Some used in real life, some that exist only to prove a point. Algortihms for fairness, for messaging systems, for big data, and really just a lot of things.

Again, although the first section really has not much to do with algorithms, it definitely is really important for anyone starting out in algorithms. I highly suggest a quick read through because it’s important to understand at a lower level what sort is sort of happening whenever we design algorithms.

Is there an order in which I should be reading this?

Again, it depends! If there is a specific topic or algorithm that you’re looking for and I have a post on it, you can just read that post. If you’re here for a more structured reading, you can probably just read things from start to end, skip around a little bit and even circle back sometimes. At the end of this post, I’ll talk about the rough structure behind this series. If possible I’d try to make the content as versatile as possible, but no promises.

There are a few considerations I have when deciding the order in which I’m writing my content:

- It’s hard for newcomers to algorithms to fully appreciate ideas in certain topics without first gaining some experience.

- At the same time, trying to give newcomers all the information that they need from the getgo is trying to do too much, too fast, at too early of a stage.

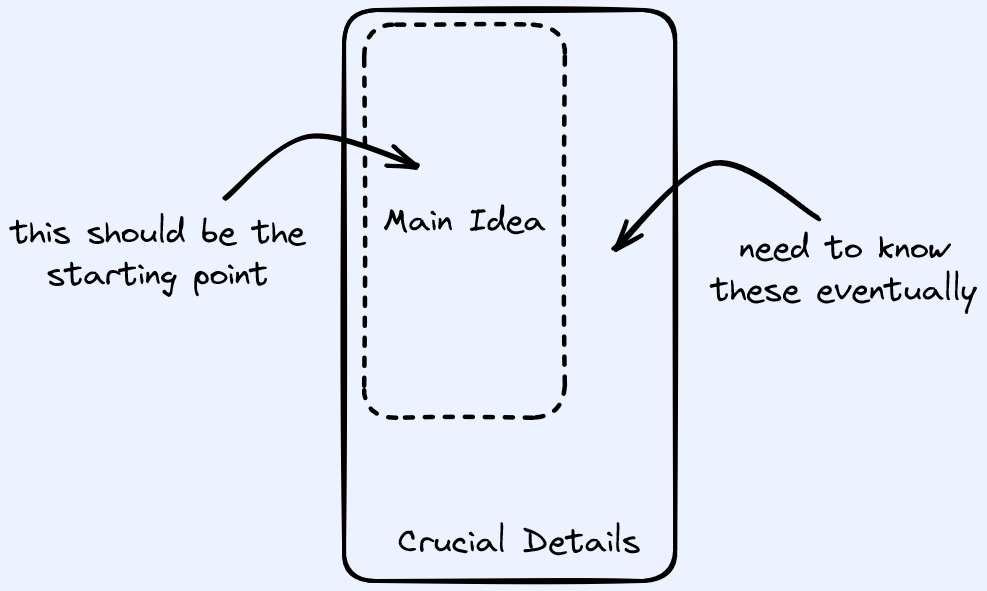

Covering the all of the relevant details is too much. But just covering the main idea

is ultimately insufficient.

Covering the all of the relevant details is too much. But just covering the main idea

is ultimately insufficient.

Because of that, the rough philosophy I have in mind (right now at least) for this “course” is as follows:

- I’ll do my best to pick and order topics so that the progression in learning makes sense.

- I’ll mention whether things actually have more nuance without actually going into details at the beginning. You may just leave a mental footnote that we will be revisiting the topic again (either in passing or in detail) for a deeper understanding.

- I’ll make simplifying assumptions but I will tell you what they are and how things might work differently. In fact, expect my next post to talk about the most important ones that we’ll be making throughout most of this content.

Furthermore, for each post (after the first section), I’ll break up the post into a few parts:

- The first part will just talk about the motivating ideas behind the post.

- The second part will start giving more concrete details.

- The third part will go in full detail as needed.

For people who just want to appreciate the ideas without the technical details, I’ll try to make it so that the first part is enough for a comprehensive sketch. For the more technically and formally inclined, the second and third parts should serve your needs.

I would still strongly suggest that everyone give the entire post a read through even if you’re just there for the idea. It’s important to have some glimpse of the nuance and intricacies that hide behind the ideas.

What are algorithms? From a layman’s perspective

Algorithms might sound like something only “tech” people do. You might have heard about it in movies or TV shows. Every time someone wants to hide the details of doing something fancy on a computer they just say “I have this algorithm that does all of it for me.”

Taken from https://www.reddit.com/r/ProgrammerHumor/comments/9wi5vy/how_to_define_algorithm/

The truth is, the plainest description for what an algorithm is, to be frank, immensely mundane. In layman terms:

(Informal) An algorithm is just a finite description of a set of steps to accomplish a given task, given some initial input or state.

I hope I’ve not actually scared you away from the study of algorithms itself. My point is, with loose enough terms, there are a lot of things that can be viewed as an algorithm.

Directions on how to get from your home to work, for example. A baking recipe. A routine at the gym, even.

All of the above generally provide a list of steps that need to be followed in sequence. For example, you might start with some ingredients, and upon finishing the steps, would arrive with some cinnamon rolls.

So in the most abstract sense, “algorithm” really is just a fancy term for “set/sequence of instructions”.

It might be more instructive at this point to ask, what isn’t an algorithm? Anything which might not be well defined, or anything that does not really set out to accomplish a goal via a set of steps, would probably not be called an algorithm.

That said, it’s pretty hard to actually draw a clear distinction right now. Luckily, I don’t think it’s all that important at this point (nor at any point) to actually do this. The irony is that, over time, as you get comfortable with algorithms, you might also come to agree that having a layman description of what an algorithm is, is really nigh on impossible, but at the same time not very important.

This isn’t to say that we should not have formal mathematical definitions for what algorithms are. In fact, that is going to be really important for us. Eventually when I come to introduce it much later on, we will talk about how mathematics has a strict sense of what an algorithm is, and how it differs from what I have mentioned above.

What are algorithms? From a computer scientist’s perspective

Alright, let’s depart from the abstract and talk about what you’re probably here for.

Almost always, when we talk about algorithms in a formal setting, algorithms are

descriptions for how to manipulate data.

The data usually comes in the form of bits that might encode integers,

floating point numbers, strings, and so on.

Here is a really simple example written in Python1:

def power(a, b):

# assumes that b >= 0

result = 1

while b > 0:

result *= a

b -= 1

return resultAlg.1 - An algorithm that raises a to the power of non-negative b.

You can think of the Python code for the example above as an implementation of an algorithm. Each algorithm is solving a respective task. The algorithm is the set of steps needed to get the task done, and we are executing the steps in Python. One could also write the same algorithm in a different programming language and it would be more or less the same algorithm if it has the same steps2.

As a whole, the study of algorithms is about trying to come up with a set of steps that given some kind of input, manipulates it so that we get some desired output. Sorting a bunch of numbers is a task. Storing a bunch of names is a task. Trying to see if a specific number is stored in a list, is a task. In the next chapter we will talk about what kind of steps can we make, and what kind of data do we operate on.

So why study algorithms?

Often times, coming up with an algorithm is not enough, it’s important that we come up with algorithms that are efficient. Now what “efficient” means is a little complicated to explain, as you’ll see. But generally, most of the time as we come up with ideas, efficiency is a primary concern.

Most of the time, people will have to manipulate data in all sorts of ways. Being more efficient generally translates to using less time, less computer memory, and perhaps even saving electrical energy and so forth. While in truth it is actually hard to go about measuring these factors precisely, studying algorithms itself should at least help you build up a good toolset to go reasoning about any algorithm you might end up designing in the future.

Your very first algorithm

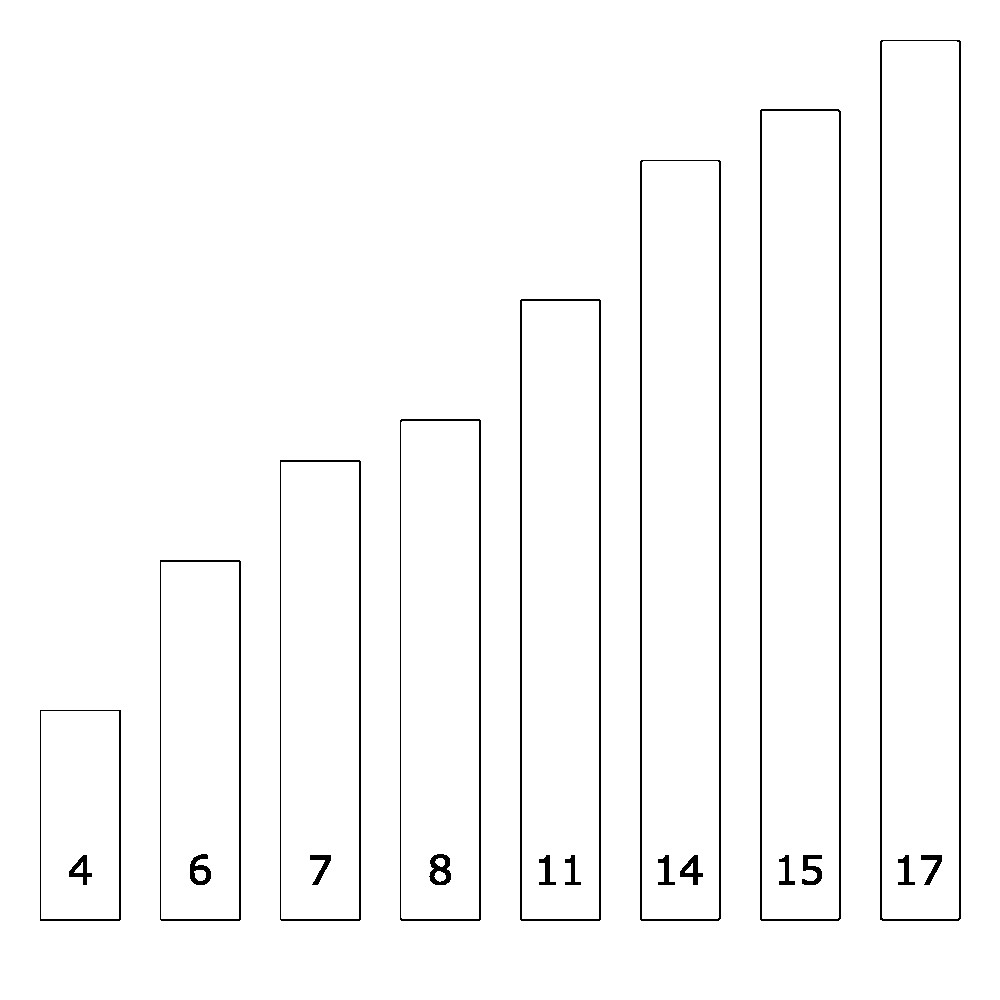

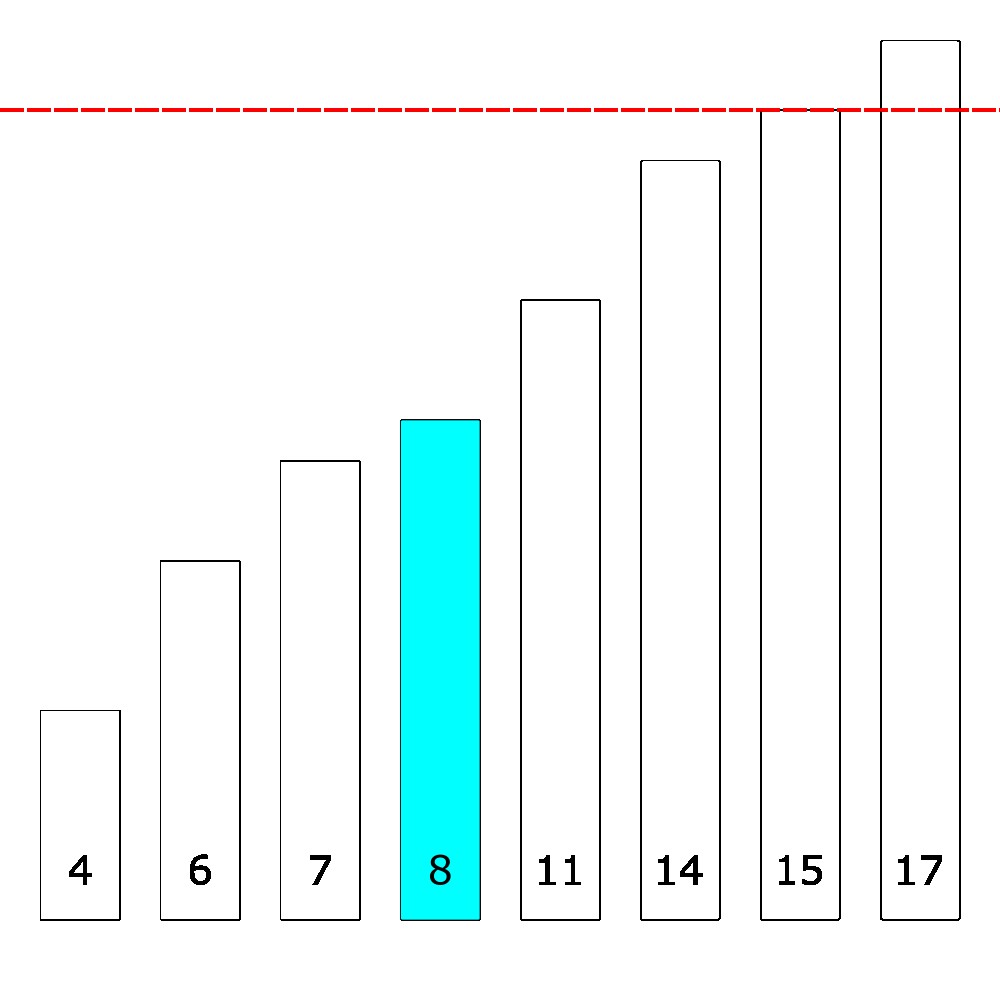

Let’s start with one of my favourite algorithms solving a really common task – binary search. Let’s say that you were given a sequence of numbers. For convenience I’ve also drawn them as boxes with heights for the sake of illustration.

And the task is that you’ll be given a number, for example, \(15\). Now it’s probably quite clear at first glance that clearly \(15\) is present in our list. That aside, I want you to focus on how you arrived at that conclusion. Did you look at every number up on that list, and check to see whether each number was \(15\)? If I gave you \(100\) numbers, how many numbers would you look at? How about if I gave you \(1000\)? \(10000000\)?

Consider the following algorithm instead, when we are given a query number like \(15\), we start in the middle and compare it against the middle element of the list, like so:

Notice how the middle element here is smaller than \(15\)? Since our list here is sorted, we know that everything to the “left” of the middle element must also be smaller than \(15\). So we now know that the only relevant portion of the list is on the right. So we can proceed to search only on the right side of the list. This sort of idea is called recursion. We’ll talk about that in detail very soon. But here’s an example implementation the algorithm in Python:

def search(array, num, left_index, right_index):

# if the array is empty

if left_index > right_index:

return False

middle_index = (left_index + right_index) / 2

# if the middle element is the same as num, we return it

if array[middle_index] == num:

return True

# if the number we're looking for is larger than the middle element,

# we search on the right half of the array

if array[middle_index] < num:

return search(array, num, middle_index + 1, right_index)

# else the number we're looking for is smaller than the middle element,

# we search on the left half of the array

else:

return search(array, num, left_index, middle_index - 1)Alg.2 - An algorithm that given an array of numbers, searches for whether num exists.

Take some time to familiarise yourself with what’s going on here. I’ve only done one “iteration” of the algorithm. After it has decided to search on the right half, what happens next? It might be worth it to try out the algorithm from yourself from start to end. Also try it on other inputs, like \(4\) or \(0\) or \(100\) and see what the algorithm does.

Now back to the main point behind this algorithm. How many numbers do you think this algorithm inspects? Since we are halving the list at each given time, if we had started with \(8\) numbers, we really only need to check \(3\) numbers at most. For a \(1000\) numbers, we only need to check \(10\) numbers.

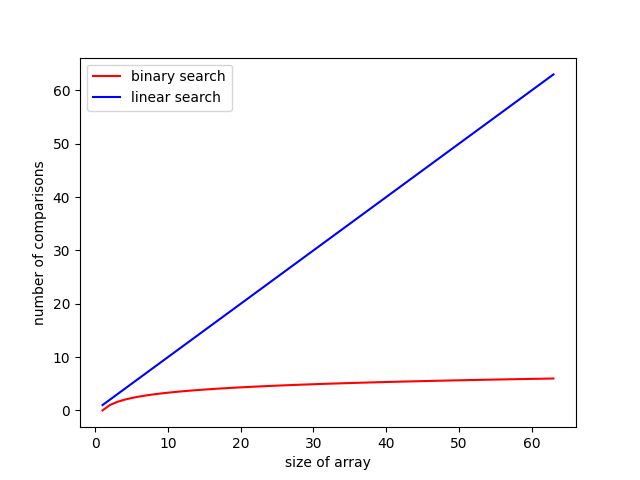

In general, if there are \(n\) numbers, we only need to check about \(log_2(n)\) numbers, where the base of the logarithm is \(2\). On the other hand, consider a more straightforward algorithm that just checks all \(n\) numbers. Here’s how that holds up comparatively against each other:

Fig.1 The number of comparisons for binary search (red), and for linear search (blue).

Notice how even with a list of size 64, there is already a marked difference between the “efficiency” of the two algorithms — the number of elements we end up comparing with is much lower for binary search rather than linear search!

Some Things to Think About

Here are some follow-up questions that are quite important to consider:

- Does the “linear” search algorithm really always take as many comparisons as there are elements? Are there good cases where the “linear” search algorithm might win out against binary search?

- What sort of assumptions are we making about the list? What if the list of numbers could not be indexed into?

- If it was not a list of numbers, but a list of something else — like English words, book names, and so on. Does binary search still work? What are we assuming about numbers that we need for this algorithm to work?

- Is \(log_2(n)\) the best that we can do for a list of size \(n\)?

- Is “number of element comparisons/accesses” really the way to measure efficiency? Are there other things we should be considering?

In due time we will go about answering some of these questions in detail. But for now it’s good to just have these in the back of your mind as we progress.

Where do we go from here?

As I’ve mentioned, the next post will be a really tall post that should cover most of the fundamentals. I highly recommend going through it so that we can all have the same mental model before starting our foray into algorithms. You don’t have to do it in one sitting. Chances are, if you’re starting out a degree in CS or already have some programming knowledge, most of what I’m including there should be somewhat familiar to you.

If you already have a strong background in computer systems, the first half of the next post will not cover anything new, but the second half covering the basics for algorithms might be.

Either way, see you in the next post!

-

Since our focus is on algorithms, there’s less emphasis on what Pythonic features are out there and often times the choices are based on what I want to focus on for the sake of algorithm exposition. ↩

-

There are some caveats to what I’ve said here but for now it is not a very important distinction right now. ↩